Has anyone watched

this video by Roger Unger at Univ of Texas? I was led to it by procrastinating and reading Malcolm Kendrick's blog (which I find excellent), in particular some

blogposts on rethinking diabetes here.

Unger is presenting research that seems to demonstrate that the centre of Type 1 is not the body's loss of insulin, but its loss of control over glucagon. ie, that while current principles of control by insulin are not wrong, current thinking about how Type 1 works is wrong.

Enjoy.

Thank you for posting this. I had never heard of Unger. I thought I had it all understood. Now I realize I understand nothing. That's good. I need to learn more.

I googled Unger and read intensively. It seems what he and UT are discovering dovetails with what

Prof. Taylor uncovered about T2 diabetes and visceral fat.

I found this news item but it's behind a pay wall so here it is in full:

MIND BLOWERS: DR. ROGER UNGER

McMullan, Dawn.

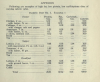

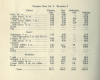

D - Dallas/Fort Worth 38.11

38.11

(Oct 2011): 69.

Abstract (summary)

TranslateAbstract

Since Frederick Banting discovered insulin as a treatment for Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in 1922 (before that, it had a 100 percent fatality rate), not much has changed.

*****

Everyone in Roger Unger's father's family had been a doctor. It only made sense that he'd go premed when he started at Yale. He can't remember considering any other option.

Unger grew up in Westchester County, outside of New York City. His father, Lester J. Unger, was a well-known doctor who invented the first direct blood transfusion instrument. While in private practice after medical school, the younger Unger had a friend who changed the course of his career - and, potentially, the lives of many living with Type 1 diabetes.

His patient, a star tennis player in the '50s, was having a difficult time managing his diabetes during the latter sets of long matches. Unger traveled with him to a major competition, trying his theory that glucagon injections could keep blood sugar levels stable. "At that time, glucagon was considered a contaminant of the insulin extraction procedure, and I felt that was very unlikely," he says. "I felt it was a true hormone, and I wanted to prove it."

He has been working on, in, and around that concept ever since.

Since Frederick Banting discovered insulin as a treatment for Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in 1922 (before that, it had a 100 percent fatality rate), not much has changed. It was such a miracle that nobody wanted to mess with it. Consider this: we discovered insulin five years before Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic. And we're still treating diabetes the exact same way.

During his studies, Banting extracted glucagon, which has the opposite effect of insulin. Unger's work in the '60s and '70s showed that a lack of insulin was accompanied by an excess of glucagon. If you suppress the glucagon, you don't need insulin, Unger says.

"The treatment from the time of Banting until today is to replace the insulin and ignore the glucagon," Unger says. "The problem with that strategy is if you give enough insulin to suppress the glucagon, you are giving too much to the rest of the body. Now what we've done is suppress the glucagon and then give low levels of insulin instead of the seesaw, roller-coaster, up-and-down glucose levels that are characteristic of every Type 1 diabetes patient. We get perfectly normal glucose levels, just like a nondiabetic."

He is now in the middle of a two-year study that is translating his work with animals to humans. If successful,

there will be a large-scale national study, and, eventually, he'll take what he's learned to Type 2 diabetes research. If it doesn't work, he jokes that he'll join the witness protection program.

"I don't want to jinx it, but all I can say is we are very hopeful," he says. "Otherwise, we wouldn't be wasting our time. I'm hopeful that all of this work is going to make a big difference for diabetes patients Until I know whether it will, there's sort of a chronic suspense. If it's no **** good, what did I do all of these years?"

*****

I don't know what happened to the large-scale national study.

️

️

38.11

38.11