German researchers have been able to detect abnormal T cell activity in babies genetically predisposed to type 1 diabetes even before they develop autoantibodies.

This means that T cell-mediated autoimmunity may develop before antibody production begins and therefore become the earliest signpost for type 1 diabetes.

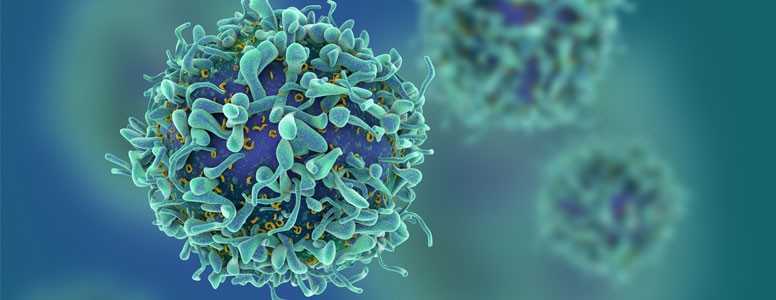

T cells are an important part of the immune system – they are involved in identifying threats to the body and removing the danger.

Autoantibodies are produced by the immune system and directed against insulin-producing cells of the pancreas in type 1 diabetes.

The peak age for diagnosing type 1 diabetes – after multiple autoantibodies appear – is between 10 and 14 years of age, but the under 5s age group has seen a steep rise in recent years.

Based on T cell activity, it could potentially be detected much earlier thanks to the research of these biologists at the Technische Universität Dresden in Germany.

The team has been following, from birth, a small number of children genetically predisposed to type 1 diabetes.

From samples of their blood cells, they probed the T cells of 12 babies who didn’t go on to develop autoantibodies and 16 babies who did.

What they found is that in about half of the infants who went on to develop autoantibodies, their T cells were not normal. By “not normal”, researchers mean that those T cells react to antigens on the surface of beta cells and get activated when they’re not supposed to.

This unusual T cell behaviour was entirely absent in infants who didn’t get autoantibodies later on.

Several hypotheses have been put forward for what controls the onset of autoimmunity, i.e., what causes immune T cells to go rogue.

It has been suggested that certain T cells may not receive full “education” in the thymus (a small organ that sits between the top of the lungs) on how to recognise and differentiate legitimate pathogens from self.

It could be linked to inconsistencies in the maturation of the newborn immune system, or possible environmental drivers of type 1 diabetes, like certain infections.

If the trial is repeated with a larger number of children, those findings could break new ground in identifying T cell-related likely signs of type 1 diabetes. This would have major implications for prevention and early intervention in type 1 diabetes.