Can we all now agree “healthy” starchy foods spike blood glucose?

Carb counting is all well and good, but as a concept it is still one step away from looking at diabetes diet advice in the purest way. This could be of particular importance to the management of type 2 diabetes.

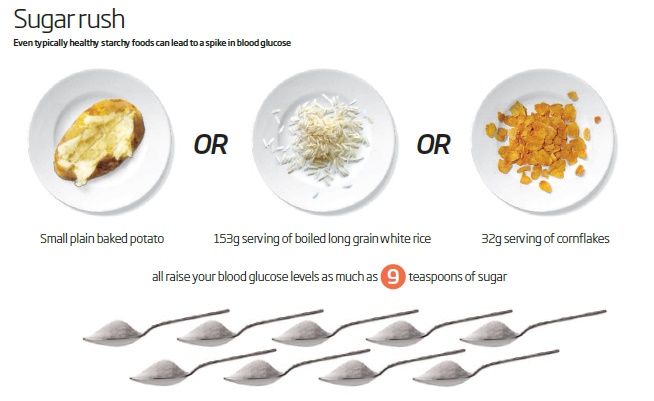

In a new paper, Dr David Unwin, Dr David Haslam and Dr Geoffrey Livesey have converted the glycemic index (GI) of some very common foods into the equivalent teaspoons’ worth of sugar.

The GI is a measure of how much a food will raise blood glucose levels, and with this study, Unwin and colleagues have made the GI accessible and understandable to the point where everyone can understand the effects of certain foods.

Eating a low-carb diet, counting carbs, and eating to a meter (where the patient has one) are all necessary skills for improving blood glucose management. But the researchers wanted to take things to the next level.

It might surprise you to see exactly how different foods can raise blood glucose. I, for one, have been trying to think back and count all the sweetcorn I ate in the last week, now knowing that per serving, it can raise blood glucose almost as much as French fries.

Representing the GI in terms of teaspoons of sugar lends the index a great deal of accessibility, with Unwin boiling everything down to a basic level that everyone can understand.

We can see a teaspoon of sugar equals 4 grams of sugar, and that a serving of basmati rice is the equivalent of 10.1 teaspoons of sugar. Through this, we can see the effect that a serving of basmati rice really can have.

I wouldn’t consider it healthy to chomp down 40 grams of sugar alongside a curry, so why eat it as rice?

Dr Unwin has focused on treating diabetes with low-carb dieting and looking at the GI in food with his patients, and in this new paper he uses his own practice as a testing ground to see how readily patients responded to a new focus on GI.

The authors wrote that it was “understood by patients and staff, helping to achieve significant improvements in diabetes control and weight. The practice as a whole compared to the average for the area was found to have; a significantly better quality of diabetes control, lower obesity prevalence whilst spending around £40,000 less per year on drugs for diabetes.”

Navigating the carbohydrate quagmire can be tricky, but hopefully everyone can agree on the basic premise of the paper. As Unwin summed up:

I wonder if we can all agree that more green veg, less high glycaemic index carbs and less snacking would be generally a good thing?

— Dr David Unwin (@lowcarbGP) May 23, 2016

This research could be a vital tool in improving the health of people with diabetes.

Eating high GI foods can cause sharp rises in blood sugar levels, which can be problematic for people with diabetes. However, eating a low-GI diet can improve your glycemic control and help you feel fuller for longer.

Unwin concluded: “Greater consideration needs to be given to the harmful effects of high-GI starchy foods in the treatment and prevention of obesity and diabetes. Patient compliance and outcomes justify our approach in a primary care setting.”

By presenting this information in an easily understandable and relatable way, Unwin’s study could help improve healthcare outcomes across the world.

Image: New Scientist