Combining screening for eye disease and liver damage in people with type 2 diabetes can “kill two birds with one stone”, latest research has revealed.

A new study from the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden has highlighted that screening for eye disease can also detect liver fibrosis – a build-up of scar tissue in the liver which can lead to cirrhosis or cancer.

Fatty liver disease affects more than half of people living with type 2 diabetes, putting them at increased risk of developing liver fibrosis.

- Type 2 diabetes risk among obese people reduced by tirzepatide

- Chemical in ultra-processed foods could cause leaky gut and increase risk of type 2 diabetes

- Earlier type 2 diabetes diagnosis linked to increased dementia risk

Global recommendations say that people living with type 2 diabetes should undergo screening for the condition.

First author Professor Hannes Hagström said: “Unfortunately, severe liver disease is often detected late when the prognosis is poor.

“Since there is now an approved treatment for steatotic liver disease with fibrosis, it would be good to be able to screen diabetic patients for liver fibrosis and thus prevent severe disease.”

During the trial, the team of researchers used elastography to simultaneously screen for liver fibrosis and eye disease.

Professor Hagström said: “This would allow us to kill two birds with one stone and easily detect liver fibrosis in this patient group before it develops into cirrhosis or liver cancer.

“Our study shows that many patients with type 2 diabetes are willing to undergo such combined screening.”

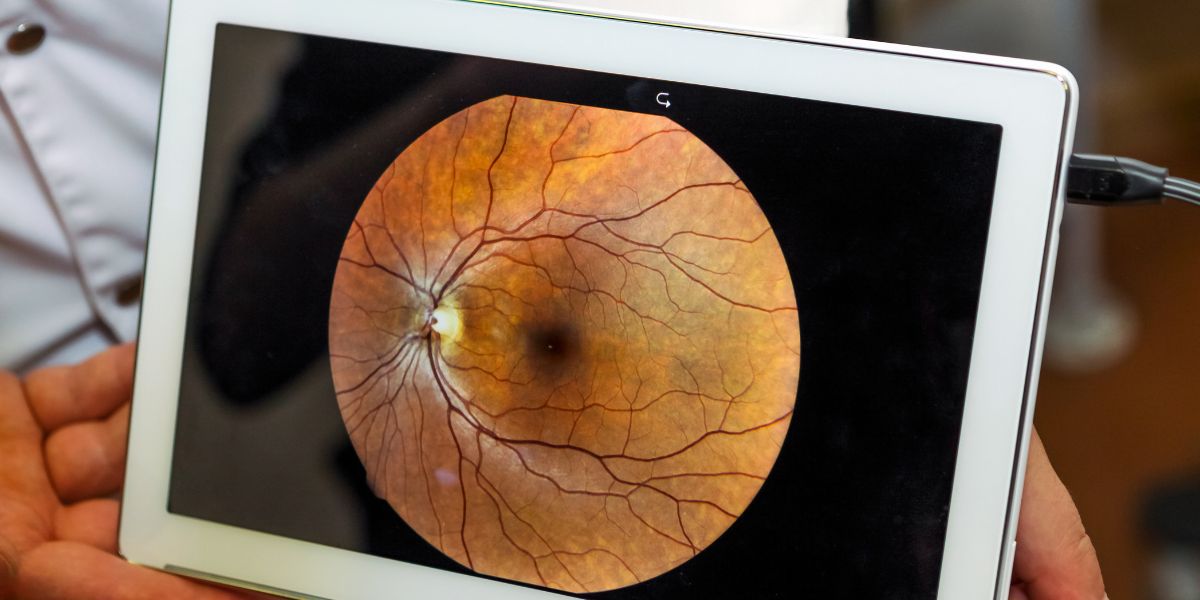

More than 1,000 people with type 2 diabetes undergoing a retina screening also agreed to have their liver examined by elastography.

- Doctors rarely use AI-assisted screening to detect diabetic retinopathy

- Eye stroke: Link between semaglutide and eye condition identified

- Rare eye condition can be triggered by weight loss jab

Roughly 7.4% of these people showed signs of liver fibrosis, and 2.9% had findings suggestive of advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis.

Professor Hagström concluded: “It shows that the method gives many false positives, partly because many people were probably not fasting as instructed at the first examination.

“The next step will be to conduct health economic analyses to see if the combined screening strategy for eye and liver disease is beneficial.”

Read the study in the journal Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology.